Off By Heart: A love letter to the Book of Common Prayer.

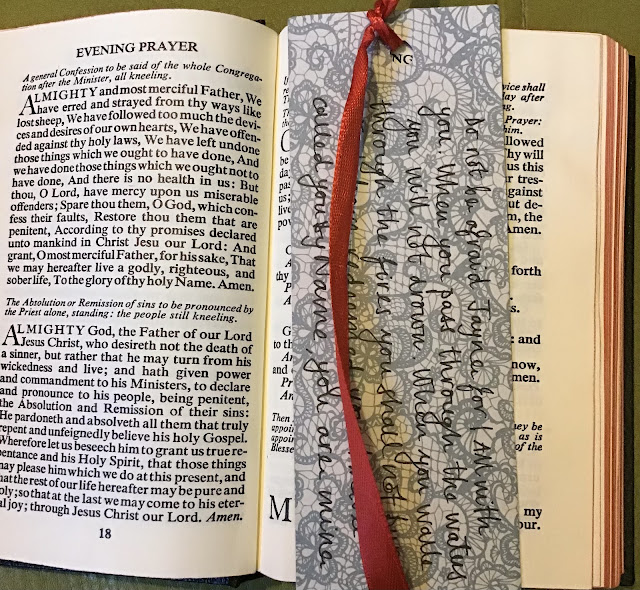

There is a small, black, leather-bound book that I keep by my bedside. The pages are well thumbed and semi-translucent, faded by time, slightly curled and fragile, like a dry oak leaf in November. If I put my nose to its spine and sniff - and why wouldn’t I? - its scent conjures up a memory of the Liddle Archive in Leeds, where as an undergraduate I once spent many hours poring through the letters of dead soldiers, mailed home from the trenches. They contained splashes of mud and a lost idiom, etched in a forgotten hand. The book by my bedside is also an artefact. It’s a memory of a time long since dead, yet it still breathes when I read it.

It was given to me by a priest, shortly after I came to faith when I was 33, but I didn’t really bother to open it with any clear intention until the first lockdown in 2020. Then there was time and a goodly dollop of existential dread, prompting me to know those pages better. To explore my faith by saying the prayers that are my Anglican inheritance. What I discovered within the pages of that diminutive book was unchanging timelessness amidst a turbulent transition, routine and stability during unprecedented chaos, and uplifting beauty at a time when all was flat and dull. In recent weeks, amidst a period of deep sadness and distress, that little black book has come into its own again.

The ancient Greeks believed that the heart was the seat of intelligence and memory, as well as emotion, as did the Hebrews, who used the word heart to denote the human will. This ancient belief is possibly the origin of the phrase, to learn by heart or off by heart. Recently, I watched a retired priest in his nineties preside at a prayer book Eucharist, intoning the whole service entirely from memory. What was learned as a boy and a young man, and oft repeated as a serving Priest, had never been forgotten. Newer discoveries, like my name for example, continued to escape him entirely. I’ve encountered elderly women who can recite the collects and can join in with Evensong without needing to refer to the book because they practised it so often during childhood and absorbed it along with their times tables. Once a prayer book Anglican, always a prayer book Anglican.

If something is known in our heart of hearts, then it is truly known: as Diarmaid MacCulloch so poetically puts it, to know it so well that the words become polished as smooth as a pebble on the beach. Polished prose you can keep in your pocket, and caress with your fingertips and clench in the palm of your hand like a talisman. Or, to use Eamon Duffy’s sideways compliment: “Cranmer’s sombrely magnificent prose, read week by week, entered & possessed the laity’s minds & became the fabric of their prayer, the utterance of their most solemn & vulnerable moments.”

I’ve rarely felt more solemn and vulnerable than I have of late. When all the words that usually come so easily are spent, there is a little book of prayer language written just for that purpose. Uttered by multitudes over hundreds of years, often by rote, off by heart, even when it’s completely broken. When I crave the comfort of simplicity and predictable routine, and extempore prayer is impossibly onerous, this book speaks in my stead. It doesn’t seek to coddle me nor deny the shadow side of my earthly life, but instead offers me the stark truth: that if salvation is to mean anything at all, then I need to know that one of the things I need saving from is myself. I have repeatedly lost my life and found it again within those pages. Lighten our darkness, we beseech thee, O Lord and there is no health in me, hits particularly hard when you’ve reached rock bottom, the very depths of the miry pit.

I’ve heard the language described as arcane and not accessible for ordinary people, but as someone who has been described as common a fair few times, it speaks to my heart like it’s my first and only tongue. I’m not learned or scholarly. I don’t speak any other languages and I don’t understand most Latin, yet when I read this book I can utter the same words to God penned long ago by a master liturgist and it belongs to me. It is mine as much as it is the property of Oxford dons and Masters of Choirs, linguists and clever writers of note, because its treasures transcend boundaries of class and status, and we do people a disservice if we assume that traditional language can’t belong to us all.

When I’m feeling emotionally fragile, a plethora of options and choice is stressful and bewildering. Reaching for just one book is as consoling as slipping my feet into a pair of worn but well-loved slippers. It’s liturgical hygge. That Cranmer’s great project to streamline liturgy and prayer has been largely replaced by something which is labyrinthine in its sundry variations and endless choices, is a sad irony indeed.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be an either or situation. For example, I can appreciate the convenience of the Daily Prayer App on my phone, despite the fact that the last time I used it, one of my kids WhatsApped to say that the dog had been sick – not something you need to know about when you’re half way through the Benedictus. Whereas moments spent with my dainty and delightfully pungent BCP are valuable moments away from that blasted device and its vampiric demands upon my time. And I suppose I will one day make use of the convenient new curate’s Common Worship bundle – all seven volumes of it – that currently sits gathering dust on my bookcase. Just not today, please Lord.

For now, I will retreat to the tiny sanctuary that I’ve created beside my bed. I have a door I can close and a candle ready to light. Ever practical, I reckon Cranmer would be horrified at the way I’ve spiritualised his somber verse, but for me it remains a paradigm for hope. As I read, certain phrases assert themselves causing my chest to constrict with a tiny spasm of pain:

“Give unto thy servants that peace which the world cannot give…because there is none other that fighteth for us, but only thou, O God…”

And I find myself reflecting that the ancient Greeks and Hebrews may not have been so wrong about the heart after all.

Thank you. It was beautiful. I’m glad you’re writing again.

ReplyDeleteTotally agree with all you have said, thank you

ReplyDeleteOnly those things at we know by heart, truly inhabit our hearts...

ReplyDeleteJust beautiful, thank you xx

ReplyDeleteSo agree with all you have said;)

ReplyDeleteBeautiful, Jane!

ReplyDeleteI've just read your piece in the Church Times. In spite of my surname (for which I apologise, but I honestly haven't made it up) I'm a Quaker who used to be an Anglican. I was introduced to the Book of Common Prayer at the age of about 10 as a choir kid in a fairly underprivileged part of Sunderland. Once I'd cottoned on tp the fact that (eg) "Prevent us" means "Go before us", I took to the language without having to make any particular effort to do so. Inevitably, when I learned that much of the text 1662 was based on the 1549 and 1552 texts by Thomas Cranmer (no relation) that quickened my interest – but I instinctively recognised the language for what it was and is: brilliant, balanced English prose written by a master. (That's enough burbling -Ed.)

ReplyDelete